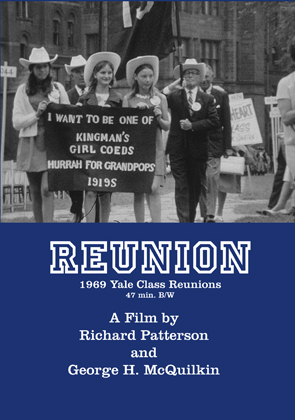

Reunion

1969 Yale Class Reunions

A Film by Richard Patterson and George McQuilkin

In 1969 George McQuilkin and I went to Yale reunions with a 16mm camera and a tape recorder. The result was a 47-minute film composed of impressionistic vignettes ranging from poignant to surreal capturing not only the diverse aspects of the event but also a moment on the cusp of a culture. 1969 was the year that Yale went co-ed and began offering a major in Afro-American Studies. The “student movement” fostered by the civil rights movement and the protest against the Vietnam War had hit Yale, but the old Yale was still very much in evidence at gatherings of classes from 1909 to 1964.

George and I had been freshman roommates at Yale. After college we each embarked upon filmmaking as a career. George went to the cinema school at USC and immediately upon graduation began working in educational and documentary films. I enrolled in a film school in London but ended up as a cameraman in the army thanks to my local draft board. We reconnected when I came to Los Angeles to attend UCLA film school in 1968. I do not recall the specific conversations, but it does not surprise me at all that our response to news of an upcoming class reunion was to see an opportunity to make a film. We were both very excited about film as a form of creative expression, and believed that any human event could be the subject of an interesting film. Part of this was simply youthful enthusiasm; part of it was the times. The Sixties had brought a flood of interest in film as an art form. It is perhaps indicative of something that George and I had both majored in philosophy.

The plan we came up with was simply a free form approach in which George would record sound and I would shoot film. During the previous decade there had been a revolution in camera and recorder technology, the impact of which is a little hard to appreciate these days when a cell phone can record better images than a studio television camera could record only a few years ago. The 16mm Éclair Noiseless Portable Reflex camera and the Nagra tape recorder made possible the documentaries of the Maysles Brothers and Frederick Wiseman as well as a host of other “direct cinema” or “cinema vérité” films in which a minimal film crew could capture events spontaneously and on the fly. We figured we would go back to reunions, get the lay of the land and simply follow our noses. We also decided to interview some alumni in Los Angeles about their feelings about reunions or Yale in general, and we deliberately sought out atypical alumni.

We contacted the alumni office at Yale to let them know that we were interested in making a documentary on the class reunions, and I believe it was the alumni office who put us in touch with Chet LaRoche as a possible source for a grant to cover our out-of-pocket expenses. Chet LaRoche was a member of the class of 1918 S, which had just had its 50th reunion. He was the head of an advertising agency and a very active supporter of collegiate football as well as Yale. He agreed to provide something like $4,000 to cover the cost of equipment rental, rawstock and processing. He and the alumni office were content to let us make whatever film we wanted to make provided we put a disclaimer at the head of the film saying that the film represented our impressions and not the views of the university, the alumni office or Chet’s class.

I remember surprisingly little about the week we spent in New Haven shooting and recording even though it was an intense experience. I do not recall how we decided when to split up and what events to cover together. The main thing I remember about shooting the footage was that the camera had a rotating viewfinder that let me sit in a chair and appear to be looking down at the camera in my lap while I was in fact filming someone across the room. Much of the time I think I felt I was stalking prey, trying to be as unobtrusive as possible, even though there are clearly moments when my subjects were conscious of being filmed. Some of what George recorded may have been said by people unaware that they were being recorded, but for the most part George’s genial interactions with his subjects enabled them to relax and engage in a genuine exchange without being overly conscious of the microphone. Some obviously relished the idea that they were being recorded for posterity.

We were able to edit the film at Churchill Films, the educational film production company where George worked. By the time the film was almost finished I had begun to get involved with the American Film Institute, and the final sound mix was done by Alan Splet at the new AFI facility. Alan had come to the AFI with David Lynch and later won an Academy Award for his sound design work.

Looking at the film 45 years later I see it as a piece of cultural anthropology or ethnographic filmmaking. During the editing George once compared the film to Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji, and I think we felt from the beginning that a series of discrete impressionistic vignettes was the most honest way to convey a sense the diverse aspects of the event. We wanted the sound and the picture to carry equal weight and often used a kind of counterpoint in which what you see and what you hear pull you in different directions and alter the impact of each other. There is also a kind of playfulness in the film that has more to do with our fascination with film than with the event of reunions. The mention of a need for a gun is allowed to stand without any explanation or further context simply because it forces the viewer to realize he is not getting the whole picture and conjures up completely unexpected possibilities.

Mostly though the film captures a very specific sub-culture at a time when it is going through a radical change. While George and I may have sympathized with some of the skepticism about reunions as a fund raising event and an occasion for the revival of adolescent status consciousness and competition, I think it is clear from the film that we had a real affection for the people and rituals associated with a Yale reunion. Perhaps our sympathies were attached to the extremes and the film resonates with this tension. Clearly the older alumni are the more appealing human beings in this study but our own youth let us to identify with the students who were rebelling against “the establishment.” It was our youth and our iconoclasm which enabled us to try to make a virtue out of the fact that there was not enough light to film properly in a lecture hall and to celebrate the arrival of Afro-American studies with an image that may convey some of the threatening sense of change felt by older alumni.

If I had to choose one moment which goes directly to the heart of the matter, it would be the scene in which the member of the class of ’44 wearing his goofy reunion hat introduces his kids to a professor he obviously admires. I think it taps into my own sense of the intergenerational bonds fostered by Yale and the way in which Yale professors were surrogate father figures ushering me into the world of ideas and passionate commitment.

– Richard Patterson

George and I had been freshman roommates at Yale. After college we each embarked upon filmmaking as a career. George went to the cinema school at USC and immediately upon graduation began working in educational and documentary films. I enrolled in a film school in London but ended up as a cameraman in the army thanks to my local draft board. We reconnected when I came to Los Angeles to attend UCLA film school in 1968. I do not recall the specific conversations, but it does not surprise me at all that our response to news of an upcoming class reunion was to see an opportunity to make a film. We were both very excited about film as a form of creative expression, and believed that any human event could be the subject of an interesting film. Part of this was simply youthful enthusiasm; part of it was the times. The Sixties had brought a flood of interest in film as an art form. It is perhaps indicative of something that George and I had both majored in philosophy.

The plan we came up with was simply a free form approach in which George would record sound and I would shoot film. During the previous decade there had been a revolution in camera and recorder technology, the impact of which is a little hard to appreciate these days when a cell phone can record better images than a studio television camera could record only a few years ago. The 16mm Éclair Noiseless Portable Reflex camera and the Nagra tape recorder made possible the documentaries of the Maysles Brothers and Frederick Wiseman as well as a host of other “direct cinema” or “cinema vérité” films in which a minimal film crew could capture events spontaneously and on the fly. We figured we would go back to reunions, get the lay of the land and simply follow our noses. We also decided to interview some alumni in Los Angeles about their feelings about reunions or Yale in general, and we deliberately sought out atypical alumni.

We contacted the alumni office at Yale to let them know that we were interested in making a documentary on the class reunions, and I believe it was the alumni office who put us in touch with Chet LaRoche as a possible source for a grant to cover our out-of-pocket expenses. Chet LaRoche was a member of the class of 1918 S, which had just had its 50th reunion. He was the head of an advertising agency and a very active supporter of collegiate football as well as Yale. He agreed to provide something like $4,000 to cover the cost of equipment rental, rawstock and processing. He and the alumni office were content to let us make whatever film we wanted to make provided we put a disclaimer at the head of the film saying that the film represented our impressions and not the views of the university, the alumni office or Chet’s class.

I remember surprisingly little about the week we spent in New Haven shooting and recording even though it was an intense experience. I do not recall how we decided when to split up and what events to cover together. The main thing I remember about shooting the footage was that the camera had a rotating viewfinder that let me sit in a chair and appear to be looking down at the camera in my lap while I was in fact filming someone across the room. Much of the time I think I felt I was stalking prey, trying to be as unobtrusive as possible, even though there are clearly moments when my subjects were conscious of being filmed. Some of what George recorded may have been said by people unaware that they were being recorded, but for the most part George’s genial interactions with his subjects enabled them to relax and engage in a genuine exchange without being overly conscious of the microphone. Some obviously relished the idea that they were being recorded for posterity.

We were able to edit the film at Churchill Films, the educational film production company where George worked. By the time the film was almost finished I had begun to get involved with the American Film Institute, and the final sound mix was done by Alan Splet at the new AFI facility. Alan had come to the AFI with David Lynch and later won an Academy Award for his sound design work.

Looking at the film 45 years later I see it as a piece of cultural anthropology or ethnographic filmmaking. During the editing George once compared the film to Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji, and I think we felt from the beginning that a series of discrete impressionistic vignettes was the most honest way to convey a sense the diverse aspects of the event. We wanted the sound and the picture to carry equal weight and often used a kind of counterpoint in which what you see and what you hear pull you in different directions and alter the impact of each other. There is also a kind of playfulness in the film that has more to do with our fascination with film than with the event of reunions. The mention of a need for a gun is allowed to stand without any explanation or further context simply because it forces the viewer to realize he is not getting the whole picture and conjures up completely unexpected possibilities.

Mostly though the film captures a very specific sub-culture at a time when it is going through a radical change. While George and I may have sympathized with some of the skepticism about reunions as a fund raising event and an occasion for the revival of adolescent status consciousness and competition, I think it is clear from the film that we had a real affection for the people and rituals associated with a Yale reunion. Perhaps our sympathies were attached to the extremes and the film resonates with this tension. Clearly the older alumni are the more appealing human beings in this study but our own youth let us to identify with the students who were rebelling against “the establishment.” It was our youth and our iconoclasm which enabled us to try to make a virtue out of the fact that there was not enough light to film properly in a lecture hall and to celebrate the arrival of Afro-American studies with an image that may convey some of the threatening sense of change felt by older alumni.

If I had to choose one moment which goes directly to the heart of the matter, it would be the scene in which the member of the class of ’44 wearing his goofy reunion hat introduces his kids to a professor he obviously admires. I think it taps into my own sense of the intergenerational bonds fostered by Yale and the way in which Yale professors were surrogate father figures ushering me into the world of ideas and passionate commitment.

– Richard Patterson